|

|

FRED SMITH - Federal Express Renegade by Kaya Morgan

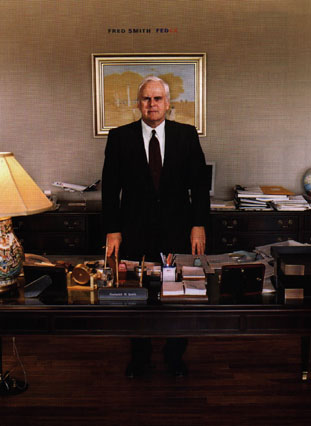

For Fred Smith, transportation is in his blood. As the founder, president and CEO of Federal Express with over 22 billion in annual revenue, he has single-handedly run the company for over 30 years, taking it from the brink of extinction back to rally high with returns for stockholders, and putting him on the Forbes list of richest people, top 400 in America, and the highest paid executives consecutively since 1999.

For Fred Smith, transportation is in his blood. As the founder, president and CEO of Federal Express with over 22 billion in annual revenue, he has single-handedly run the company for over 30 years, taking it from the brink of extinction back to rally high with returns for stockholders, and putting him on the Forbes list of richest people, top 400 in America, and the highest paid executives consecutively since 1999.

The Smith family originally migrated from England to help found the colony of Georgia. Grandfather, Captain "Jim Buck" Smith, was a steamboat operator on the Mississippi and Ohio rivers. Father, James "Frederick," Smith, an ex-steamboat clerk, and an expert salesman, selling trucks in the Texas oil boom towns. Hired on by the Memphis Motor Company, he became an agent for a variety of automobile lines, eventually founding the Dixie Greyhound Bus Lines. With enormous profits rolling in, father Fred was always on the lookout for new places to spend or invest his wealth. He bought a cotton plantation, raised pedigreed beef and owned the chain of Toddle House restaurants. But he credited his success on the premise that if you instill in your employees a feeling that a share of the success will be a credit to him, you will produce a loyal follower — an adage that later proved to also be true for his son.

The younger of two children, Frederick Smith learned early on the challenges of life. His father died when he was only four, and at eight, he had Calvá-Perthes, a disease that interrupted the blood blow to his right thigh bone, effecting its development. Although he spent two and a half years on crutches, boyhood summers were spent near Jackson on the farm of his uncle Arthur Wallace, a sort of father figure to him.

At fifteen he enrolled in the college prep Memphis University School where he joined two other 15-year-old MUS classmates, and with $5,000 borrowed from their parents, opened a recording studio. Gregarious and popular, he was eager to dig into business for himself but at his mother's urging, enrolled at Yale University in the fall of 1962. He arrived in New Haven, Connecticut somewhat sensitive about being a southern boy, taking along a Confederate flag, which he proudly hung on his dormitory wall. He went out for football, was a member of Skull and Bones, became a disk jockey at the campus radio station WYBC, and joined the Marine Corps reserve assigned to the student platoon leader training program. But it was the twelve or fifteen pages Fred typed up for his 1965 term paper in Economics 43A that became the legendary outline for Federal Express.

When Smith graduated from Yale in 1966, his commission as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Marine Corps was waiting as his reward for the hundreds of hours spent in platoon leader class. He quickly shipped out to Vietnam and joined the largest search-and-destroy battalion. Later, he related that once an enemy bullet severed the chin strap of his helmet without as much as giving him a scratch.

Fred Smith returned to the U.S. with a burning ambition to do something constructive. So, when he received the first installment of his trust inheritance — shares of Greyhound stock, he promptly turned it into $750,000 in liquid assets. He joined an old school chum looking for a partner to buy Arkansas Aviation Sales at Little Rock municipal airport, and the die was cast. Aviation, he realized, intrigued and satisfied him. Under his leadership, the company prospered, doing $9 million in revenue in the first two years. Smith obviously had the same natural knack of effective salesmanship that had launched his father to quick success. But it was his frustration in the inability of timely air freight shipments of spare airplane parts they desperately needed that really spurred him on to his future fate.

Fred Smith returned to the U.S. with a burning ambition to do something constructive. So, when he received the first installment of his trust inheritance — shares of Greyhound stock, he promptly turned it into $750,000 in liquid assets. He joined an old school chum looking for a partner to buy Arkansas Aviation Sales at Little Rock municipal airport, and the die was cast. Aviation, he realized, intrigued and satisfied him. Under his leadership, the company prospered, doing $9 million in revenue in the first two years. Smith obviously had the same natural knack of effective salesmanship that had launched his father to quick success. But it was his frustration in the inability of timely air freight shipments of spare airplane parts they desperately needed that really spurred him on to his future fate.

During 1970, Fred effectively worked himself into Little Rock's business circles, becoming especially close to the Worthern Bank. On fire with his newest brainchild, he landed a rare meeting with the Federal Reserve Board in order to build the nucleus of his airplane network by proposing a future contract for overnight air express services. He also felt that his air express plan could be a beneficial investment opportunity for the family trust. With the support of sister, Fredette, on May 28, 1971, Smith presented the family trust, Frederick Smith Enterprise Company board, in Memphis with his plan for his Federal Reserve flights. He announced that he was investing $250,000 of his own money, and asked the board for a matching $250,000 to make the trust his partner.

The proposal was unanimously adopted and on June 18th, at age 27, he incorporated his new Federal Express Corporation in Delaware, certain that using the name "Federal" would ensure his contract from the Federal Reserve System.

The trust board promptly backed his additional request to guarantee a $3.6 million loan from the National Bank of Commerce of Memphis (the trustee) to buy his first two Falcon jets — what Fred later referred to as his 550-mile-an-hour delivery trucks. His first big business learning curve, the Federal Reserve said no, only to adopt his plan independently at a later date, nightly moving 13.2 million checks through five main hubs themselves. In the late summer of 1971, Fred watched his entrepreneurial plan collapse with his two Falcon jets lying idle on the hangar floor.

Try as he could, meeting after meeting met with negative reactions from potential investors. He had a couple of purple, orange and white Federal Express jets, a mini-size corporate staff but he didn't yet have the start-up capital he needed, nor the market data to lure investors to his door. Unlike most businesses, you couldn't start small and grow over time. From the very beginning, he had to build an entire network which called for 25 cities to make it work. In order to lock up enough planes for his fleet, Fred flew to New York and signed a contract to buy 23 more Falcons from Pan Am for a total of $29.1 million, agreeing to accept delivery of one plane a week beginning September 28, 1972.

Confident that he could nightly fill his proposed fleet of 25 Federal Express jets, the annual revenue would be almost $67 million, leaving a gross profit before taxes of almost $43 million. His enthusiasm made it appear almost certain. Described as a "nitpicker," having his hand in every aspect of the business, he worked for three or four years with only six hours off one year for the Christmas Eve and Christmas Day.

Confident that he could nightly fill his proposed fleet of 25 Federal Express jets, the annual revenue would be almost $67 million, leaving a gross profit before taxes of almost $43 million. His enthusiasm made it appear almost certain. Described as a "nitpicker," having his hand in every aspect of the business, he worked for three or four years with only six hours off one year for the Christmas Eve and Christmas Day.

His efforts became more and more stymied by the red tape at Little Rock's municipal airport. On the other hand, Memphis, his old hometown, was willing to go all out to get the FedEx hub. Smith quickly made the decision to pull up stakes and move to Memphis. But soon his delinquent option to buy the 23 Falcons that were urgently needed to establish the nationwide air express made him come up with the idea to offer Pan Am warrants to purchase FedEx stock at a later date at a bargain price. They must have thought he was on the right track because his offer was accepted and the remainder of needed capital followed from institutional investors.

However, the final kick came when on January 31, 1975, Smith was indicted for using a forged document to obtain a $2 million bank loan. Another blow came shortly before midnight on that same day when while driving home from his office at the airport, engulfed by his personal crisis, he hit and killed a 54-year-old black handyman, leaving the scene, unaware he had ever hit the man. Fortunately, an off duty policeman was directly behind him and witnessed the entire incident, or Smith's story might not have ever been believed. Without question, this was probably Smith's lowest point. Fortunately, he was found not guilty in the bank fraud trial, and soon afterwards the hit-and-run charge was dismissed.

In astounding contrast with today's sophisticated, computerized, slick Federal Express operations, group couriers in the beginning months were haphazard. Stories abound about the early days when at three in the morning, with two Hertz rental cars from a nearby Holiday Inn, devoted employees met the plane to receive and deliver the inbound packages. Smith's leadership surely fired up the troops in the field. He firmly believed his company would be America's next big success story.

The essence of Federal Express's success could be said that Fred Smith was/is a brilliant guy, willing to risk his own money along with the ability and personal drive to run a company. He surrounded himself with good people who he brought into his vision, and were devoted to his cause, much like a championship football team.

Although he's been known to raise his voice on occasion, Fred Smith still operates without the need for finger pointing when things go wrong. His is a story of what can be done with ideas, energy, venture capital, and some extreme guts. His "Five Secrets of Entrepreneurial Success" include having a compelling business idea, one that is differentiated and sustainable; be a zealot; have a conservative business plan; work effectively with others; and finally, to change and grow as your business grows. Wise words from an extremely successful corporate renegade.

To find more about Federal Express, go to www.fedex.com

All rights reserved ©

Press Coverage | VentureCapital | Business Development | Venture Opportunities | Resources | Contact Us | Investor Extras | Home