|

|

THE VANDERBILT LEGACY by Kaya Morgan

Many of the stories of America's wealthiest families have often been fascinating from a social perspective. However, many of the lesser-known business practices that identify their winning combination of foresight, determination and ability to beat, and often crush the competition also rings on a similar note. If there is one common denominator, it is the passion that each brought to business, whether inspired by greed, or simply the desire to be the best.

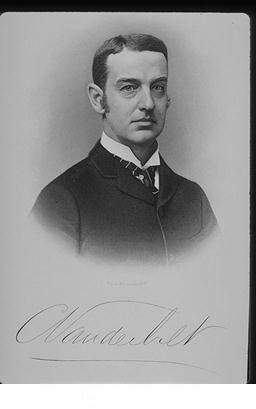

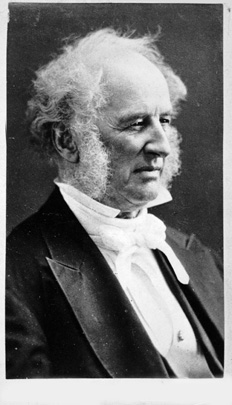

One of the most well known, Cornelius Vanderbilt (1794—1877), was born into a poor family in New York City, and quit school at age 11 to work for his father in the boating business. Setting out on his own at age 16, he earned $100 from his mother to clear and plant an 8-acre field. He then used the money to purchase a small two-masted, flat-bottomed sailing vessel (a periauger) to carry freight and passengers between Manhattan and Staten Island. Cornelius quickly built a reputation for reliability and fearlessness because he would take on any job, even in stormy weather, and he consistently charged lower rates than his competitors.

In 1817, his income began to fall due to the rise in success of the steamboat business. He responded by selling his sailing vessels, designed and built his own steamboat, ferrying passengers from New Jersey to Manhattan in violation of the monopoly. Vanderbilt undercut his competitors by charging only $1, which was below cost, compared to the monopoly price of $4, but made up his losses by raising the price of food and drink in the steamboat's bar. Vanderbilt became a key figure in breaking the transatlantic steamboat monopoly granted to Robert Fulton and Robert Livingston in the waters around New York City.

Well on his way to fame and fortune, Vanderbilt took on Daniel Drew for the service between New York and Peekskill. By cutting rates to a low of 12.5 cents, Drew was forced to withdraw. Next, he challenged the Hudson River Association by again cutting rates on their routes. They paid him off to move his operations elsewhere. By the late 1840s, he added Long Island Sound, Providence, Boston and Connecticut, running more than 100 steamboats. His company soon had more employees than any other business in the United States. And, he was credited for bringing about the rapid advance in the size, comfort and luxury of steamboats, which quickly became floating palaces under his design.

Well on his way to fame and fortune, Vanderbilt took on Daniel Drew for the service between New York and Peekskill. By cutting rates to a low of 12.5 cents, Drew was forced to withdraw. Next, he challenged the Hudson River Association by again cutting rates on their routes. They paid him off to move his operations elsewhere. By the late 1840s, he added Long Island Sound, Providence, Boston and Connecticut, running more than 100 steamboats. His company soon had more employees than any other business in the United States. And, he was credited for bringing about the rapid advance in the size, comfort and luxury of steamboats, which quickly became floating palaces under his design.

By age 40, Vanderbilt's wealth exceeded $500,000, but he still looked for new opportunities. He expanded the routes to Nicaragua, challenging the Pacific Steamship company by cutting the going rate by half. This move netted him over $1 million a year. He made money so rapidly, that in 1853 he announced that he was going to take the first vacation of his life with a tour of Europe. Before going abroad, Vanderbilt resigned the presidency and committed its management to Charles Morgan and Cornelius Garrison, who, during his absence seized control of the company. Forunately, through shrewd buying of the stock, he won it back within a few months.

Vanderbilt liked making money more than spending it. Nearing the age of 70, he decided once again that the wave of the future was in another direction — building a railroad empire. He first acquired the New York and Harlem Railroad. Next, he purchased the Hudson River Railroad, and the Central Railroad in 1867 merging the two. Soon thereafter, he acquired the Lake Shore, Michigan Southern railroads, the Canadian Southern, and the Michigan Central, creating one of the greatest American systems of transportation.

Vanderbilt's influence on national finance was truly stabilizing. When the panic of 1873 was at its worst, he paid out millions of dividends as usual. And, with the building of the Grand Central Terminal in NYC, he gave employment to thousands of men whose families would otherwise have been in the soup lines. Forever known for his countless philanthropic activities, he also gave $1 million to Central University, which then became Vanderbilt University. Upon his death, he was the richest man in the United States, leaving the bulk of his fortune of $95 million to his son, William.

All rights reserved © 2003

Press Coverage |VentureCapital | Business Development | Venture Opportunities | Resources | Contact Us | Investor Extras | Home